The Qing, China's last imperial dynasty, ruled over one of the largest empires in Eurasia at the dawn of the 19th century. Throughout the preceding century, it expanded its reach into the northwest, southwest, Tibet, and gained hegemony over Mongolia. For a long time, traditional historiography has viewed the Qing as a land-based, agrarian power with minimal engagement with the seas. Even its successful conquest of Taiwan in 1683 was seen as a one-time affair. This, the traditional narrative goes, was the reason why the Qing lost to the British in the First Opium War. Scholars today have increasingly pushed back against this view, pointing out the Qing's liberalization of ocean-going trade and its development of a naval infrastructure. Joining me today is Ronald Po, author of Blue Frontier: Maritime Vision and Power in the Qing Empire, who will talk about Qing maritime history and policy in the 18th and 19th centuries.

Contributors:

Ronald Po

Ronald Po is an Associate Professor in the Department of International History at LSE. He is a historian of late imperial China, with a focus on maritime history and global studies. His book, Blue Frontier: Maritime Vision and Power in the Qing Empire, seeks to revise the view of China in this period as an exclusively continental power with little interest in the sea. Instead, the book argues that the Qing deliberately engaged with the ocean politically, militarily, and conceptually, and responded flexibly to challenges and extensive interaction on all frontiers - both land and sea - in the eighteenth century. Professor Po joins us today to talk about his research on Qing maritime history.

Yiming Ha

Yiming Ha is the Rand Postdoctoral Fellow in Asian Studies at Pomona College. His current research is on military mobilization and state-building in China between the thirteenth and seventeenth centuries, focusing on how military institutions changed over time, how the state responded to these changes, the disconnect between the center and localities, and the broader implications that the military had on the state. His project highlights in particular the role of the Mongol Yuan in introducing an alternative form of military mobilization that radically transformed the Chinese state. He is also interested in military history, nomadic history, comparative Eurasian state-building, and the history of maritime interactions in early modern East Asia. He received his BA from UCLA, his MPhil from the Hong Kong University of Science and Technology, and his PhD from UCLA. He is also the book review editor for Ming Studies.

Credits:

Episode no. 19

Release date: September 21, 2024

Recording location: Amsterdam/Los Angeles, CA

References courtesy of Ronald Po

Images:

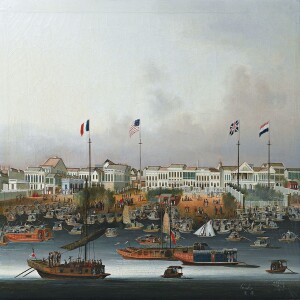

The Port of Canton (Guangzhou) in c. 1830, showing the factories of the foreign powers (Image Source)

View of Canton (Guangzhou) in c. 1665 with ships of the Dutch East India Company in the foreground (Image Source)

Chinese junk in Guangzhou, c. 1823 (Image Source)

The East India Company steamship Nemesis (right background) destroying war junks during the Second Battle of Chuenpi, 7 January 1841 (Image Source)

Select References:

Gang Zhao, The Qing Opening to the Ocean: Chinese Maritime Policies, 1684-1757 (Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press, 2013).

Hans van de Ven, Breaking with the Past The Maritime Customs Service and the Global Origins of Modernity in China (New York: Columbia University Press, 2014).

John D. Wong, Global Trade in the Nineteenth Century: The House of Houqua and the Canton System (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2016).

John E. Wills, Jr., China and the Maritime Europe, 1500-1800: Trade, Settlement, Diplomacy, and Missions (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2010).

Leonard Blussé, Visible Cities Canton, Nagasaki, and Batavia and the Coming of the Americans (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 2008).

Melissa Macauley, Distant Shores Colonial Encounters on China's Maritime Frontier (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2021).

Paul A. van Dyke, Whampoa and the Canton Trade Life and Death in a Chinese Port, 1700-1842 (Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press, 2020).

Schottenhammer, Angela, China and the Silk Roads (ca. 100 BCE to 1800 CE): Role and Content of Its Historical Access to the Outside World (Leiden: Brill, 2023).

Tonio Andrade, The Gunpowder Age: China, Military Innovation, and the Rise of the West in World History (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2017).

Wensheng Wang, White Lotus Rebels and South China Pirates (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 2014).

Xing Hang, Conflict and Commerce in Maritime East Asia The Zheng Family and the Shaping of the Modern World, c.1620-1720 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2015).

Zheng Yangwen, China on the Sea: How the Maritime World Shaped Modern China (Leiden: Brill, 2011).