The Qing Empire (1636-1912) ruled over one of the largest land empires in the world. Its territories encompassed not only what is considered today to be China proper and Manchuria, but also Tibet, Xinjiang, and Mongolia. Its subjects were composed of people belonging to different identities, of which Manchu, Han, Mongol, Tibetan, and later Uighur became the most important groups. As an empire that was composed of a small conquering elite, how did the Qing manage these different identities as its empire expanded and stabilized? What changes occurred over time? What legacy did the Qing leave on the Republic of China and the People's Republic of China in terms of how they dealt with ethnic minorities? To help answer these question, we invite Professor Pamela Crossley to talk to us about how history and identity were constructed and weaved into Qing imperial ideology.

Contributors

Pamela Crossley

Professor Pamela Crossley is the Charles and Elfriede Collis Professor of History at Dartmouth University. She specializes in the history of the Qing Empire and modern China, although her research interests also span Inner Asian history, global history, history of horsemanship in Eurasia, and imperial sources of modern identities. She is the author of eight books and numerous book chapters and peer-reviewed articles, and her book A Translucent Mirror is the winner of the Joseph Levenson Prize of the Association of Asian Studies. Additionally, she has also written commentaries for major newspapers and magazines.

Yiming Ha

Yiming Ha is a Ph.D. candidate in the Department of History at the University of California, Los Angeles. His current research is on military mobilization and state-building in China between the thirteenth and seventeenth centuries, focusing on how military institutions changed over time, how the state responded to these changes, the disconnect between the center and localities, and the broader implications that the military had on the state. His project highlights in particular the role of the Mongol Yuan in introducing an alternative form of military mobilization that radically transformed the Chinese state. He is also interested in military history, nomadic history, comparative Eurasian state-building, and the history of maritime interactions in early modern East Asia. He received his BA from UCLA and his MPhil from the Hong Kong University of Science and Technology.

Credits

Episode no. 17

Release date: March 3, 2023

Recording location: Hanover, NH/Los Angeles, CA

Transcript (by Yiming Ha and Greg Sattler)

Bibliography courtesy of Prof. Crossley

Images

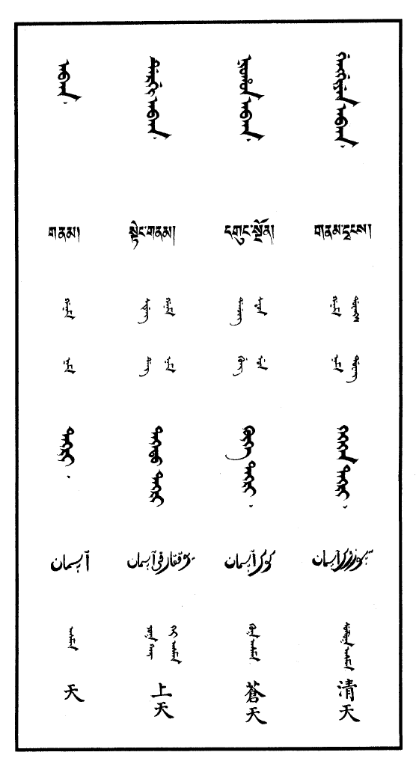

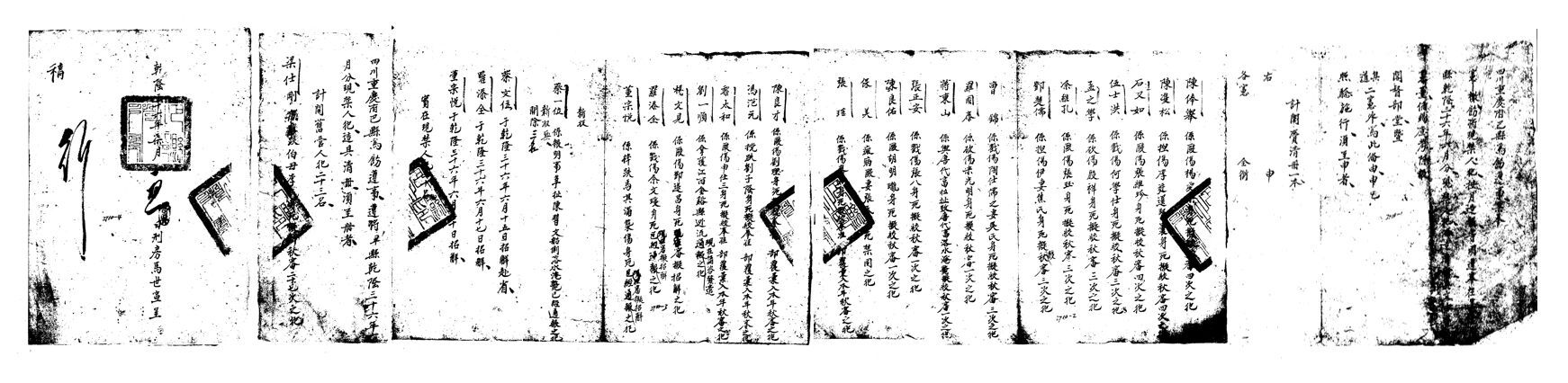

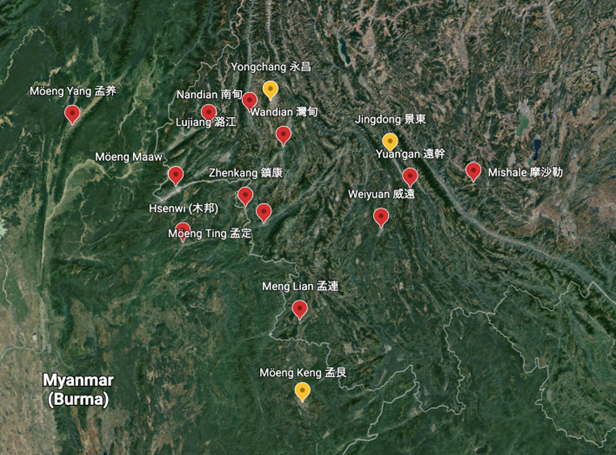

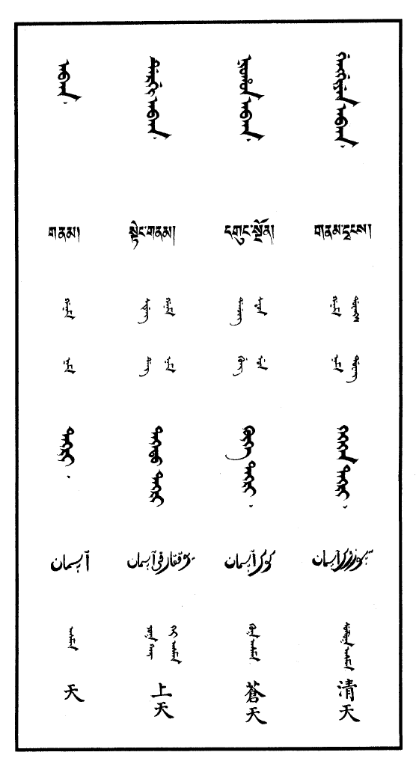

Cover Image: A page of the Pentaglot Dictionary (Yuzhi wuti qing wenjian 御製五體清文鑑), a dictionary of the major languages of the Qing compiled towards the later reign of Emperor Qianlong in the 18th century. The five languages are Manchu, Chinese, Mongolian, Tibetan, and Chagatai (now known as Uighur). (Image Source)

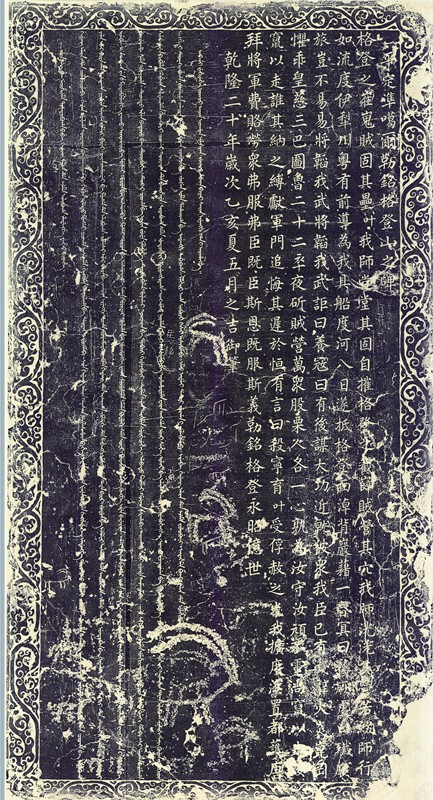

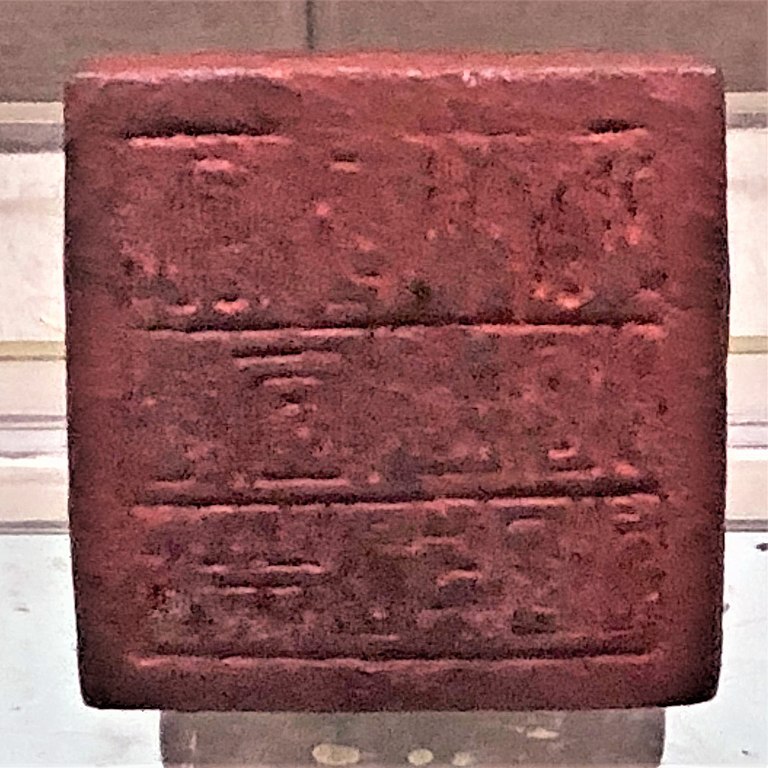

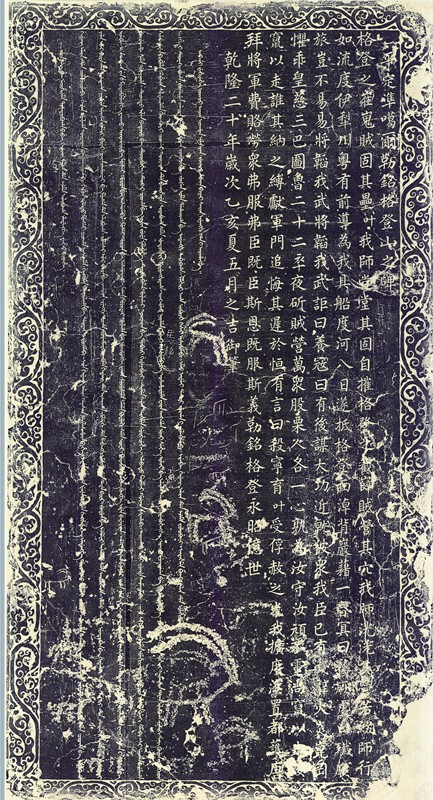

The Stele Commemorating the Victory over the Dzungars, erected by the Qianlong emperor either in the 1750s or 1760s to commemorate the Qing victory over the Dzungars in the Xinjiang region. The stele featured four languages. On the front side are inscriptions written in Classical Chinese (by the Qianlong emperor himself) and Manchu, while the reverse side features inscriptions in Mongolian and Tibetan. (Image Source)

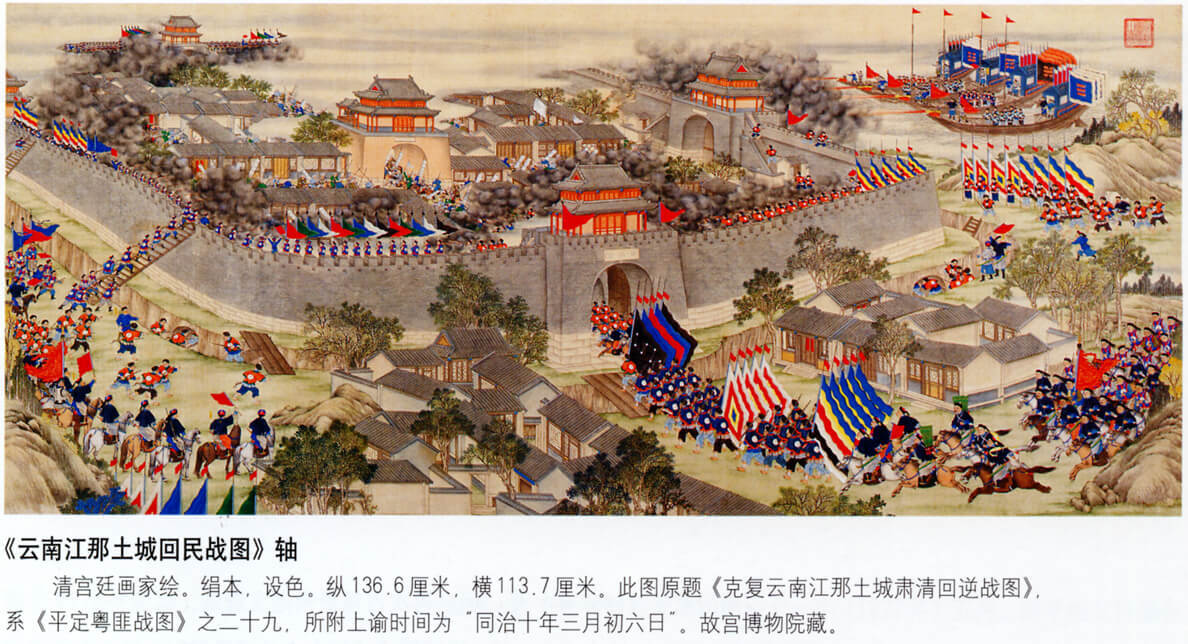

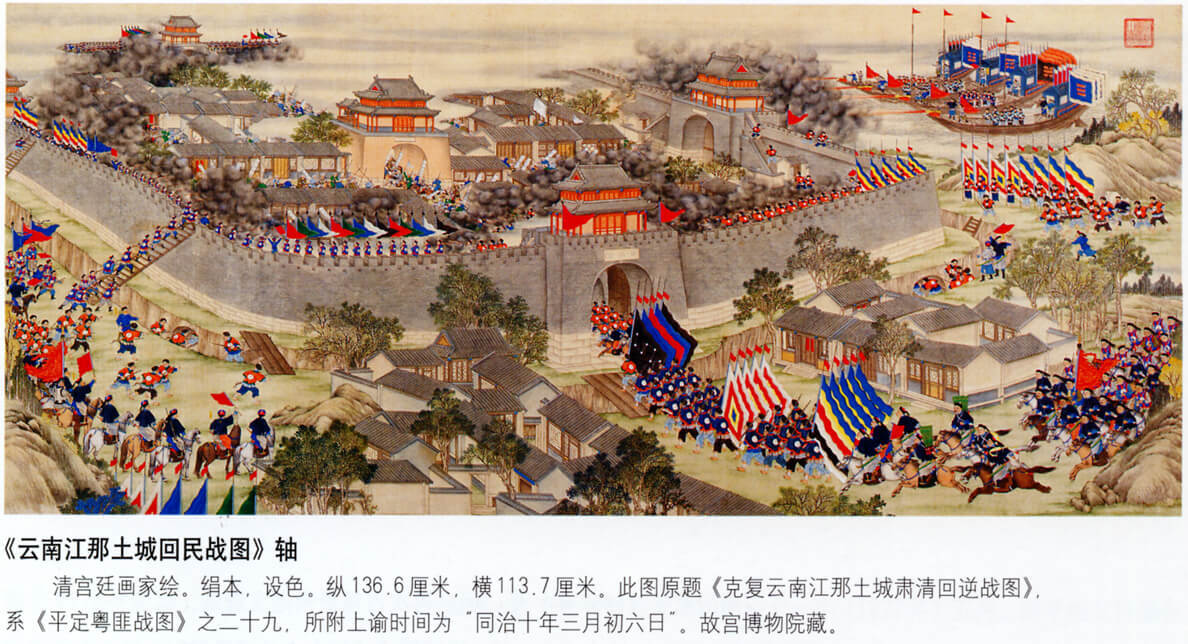

The Capture of Tucheng, a painting commemorating a Qing victory during the Panthay Rebellion in Yunnan (1856-1873). Note the five colored banner that were flown by the Qing troops. The alternate version of this flag (with the colors rearranged) later became one of the early flags of the Republic of China, with each color representing an ethnic group. Red for the Han, yellow for the Manchus, blue for the Mongols, white for the Hui (Muslims), and black for the Tibetans. (Image Source)

References

Bovington, Goardner, "The History of the History of Xinjiang" in Twentieth-Century China, 26:.2 (April, 2001): 95-139.

Bulag, Uradyn The Mongols at China's Edge: History and the Politics of National Unity (2002, Rowman & Littlefield)

Crossley, "The Cycle of Inevitability in Imperial and Republican Identities in China" in Aviel Roshwald, ed, The Cambridge History of Nationhood and Nationalism: Volume One: Patterns and Trajectories over the Longue Durée (2022, Cambridge), 301-328.

Crossley, Helen F. Siu, Donald S., Sutton, ed., Empire at the Margins: Culture, Ehtnicity and Frontier in the Early Modern China (California, 2006)

Crossley, A Translucent Mirror: History and Identity in Qing Imeprial Ideology (1999, California).

Elliott, Mark, The Manchu Way: The Eight Banners and Ethnic Identity in Late Imperial China (2002, Californai)

Perdue, Peter. C, ."Empire and Nation in Comparative Perspective: Frontier Administration in Eighteenth-Century China" in Journal of Early Modern History, 5:4 (2001, 282-304.

Jonathan D. Spence, Treason by the Book (2002, Viking).

Wu, Hung, "Emperor's Masquerade: 'Costume portraits' of Yongzheng and Qianlong" in Smithsonian Libraries, 1995, p. 25-41.