Episodes

Sunday Aug 21, 2022

Sunday Aug 21, 2022

China has a long bureaucratic history and tradition, and the Ming Dynasty (1368-1644) was no exception. The Ming was one of the largest empires in the world at the time and it established a large and complex bureaucracy to govern it. In this episode, Professor. Chelsea Wang talks to us about some of the bureaucratic practices, which might seem strange to us today, that the Ming employed to keep the empire running.

Governing China is a new series that explores the various bureaucratic institutions and administrative policies that the various Chinese dynasties employed to govern their empires.

Contributors

Chelsea Wang

Professor Chelsea Wang is an Assistant Professor of History at Claremont McKenna College. As a historian of late imperial China, Professor Wang’s research focuses on the intersection between communication and governance in premodern empires. Her current manuscript project is titled Logistics of Empire: Governance and Spatial Friction in Ming China, 1368-1644, and it examines how the Ming dynasty maintained control over its vast territories using certain administrative practices that modern observers often find counterintuitive and strange.

Yiming Ha

Yiming Ha is a Ph.D. candidate in the Department of History at the University of California, Los Angeles. His current research is on military mobilization and state-building in China between the thirteenth and seventeenth centuries, focusing on how military institutions changed over time, how the state responded to these changes, the disconnect between the center and localities, and the broader implications that the military had on the state. His project highlights in particular the role of the Mongol Yuan in introducing an alternative form of military mobilization that radically transformed the Chinese state. He is also interested in military history, nomadic history, comparative Eurasian state-building, and the history of maritime interactions in early modern East Asia. He received his BA from UCLA and his MPhil from the Hong Kong University of Science and Technology.

Credits

Episode No. 14

Release date: August 21, 2022

Recording location: Vancouver, Canada/Los Angeles, CA

Bibliography courtesy of Professor Wang

Images

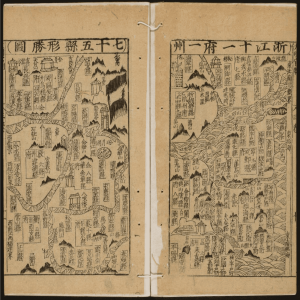

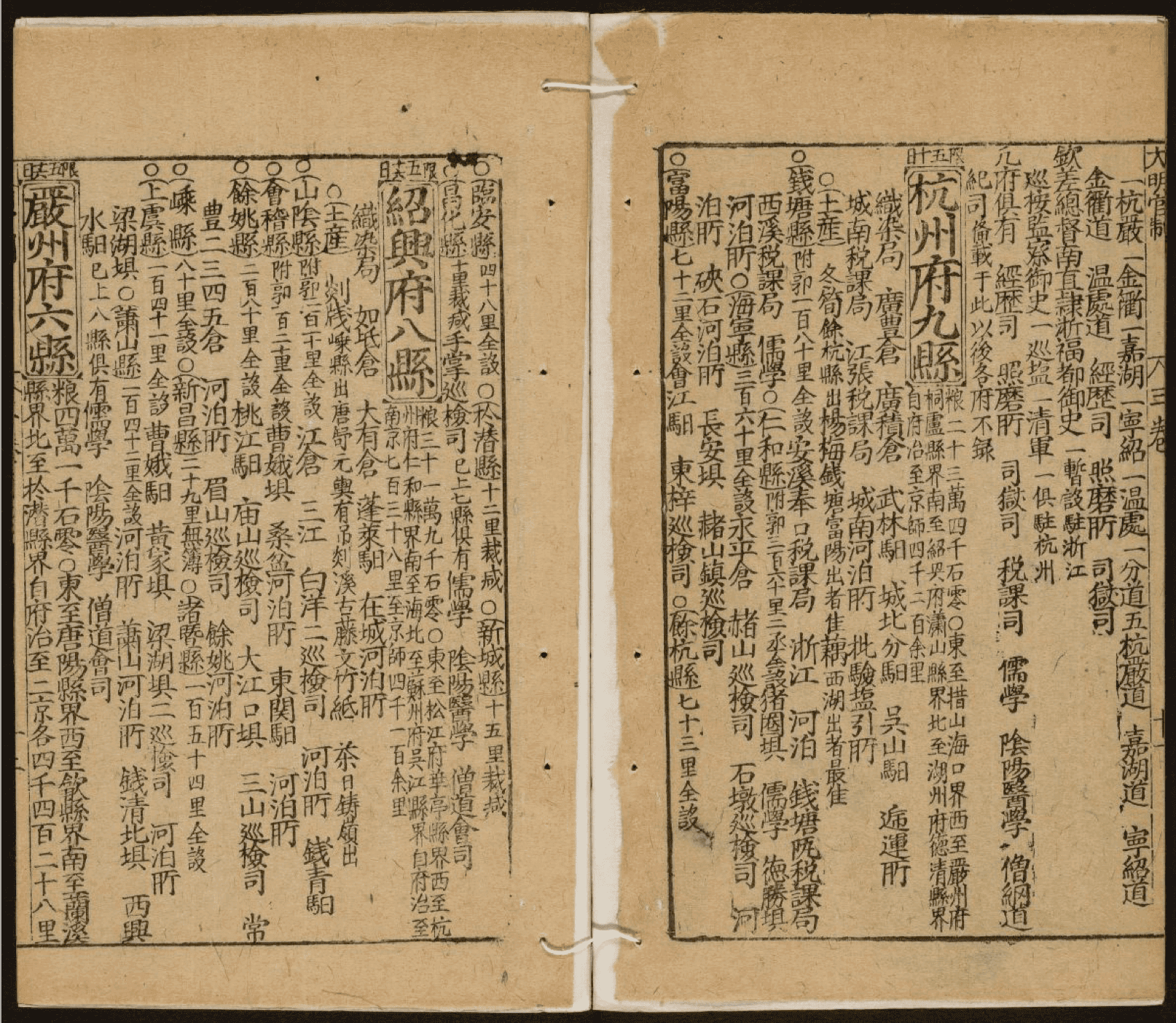

Cover Image: Section of a Ming officials' handbook showing a map of territorial government offices in

Zhejiang province (Image Courtesy of Harvard-Yenching Library's Digital Collections)

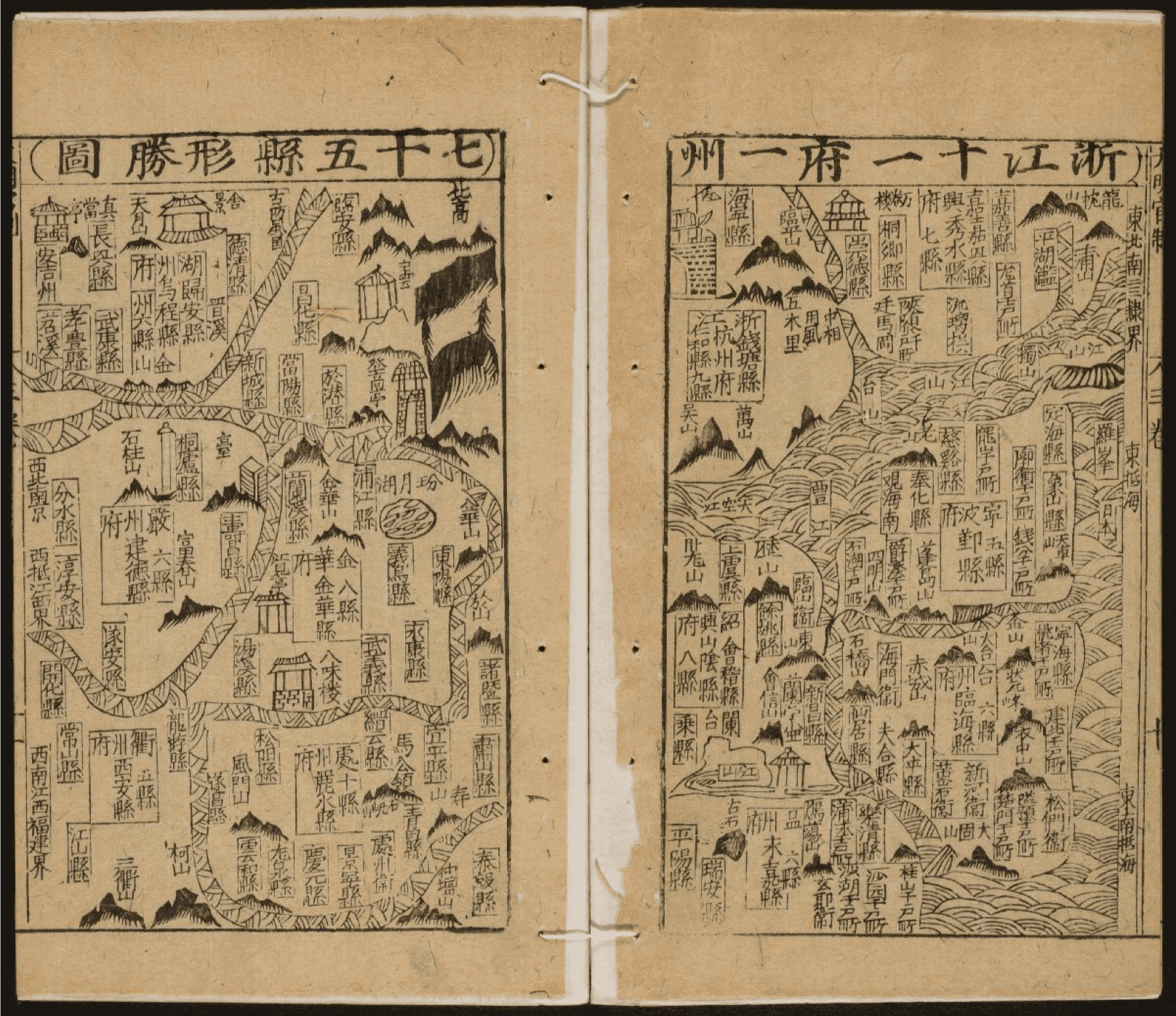

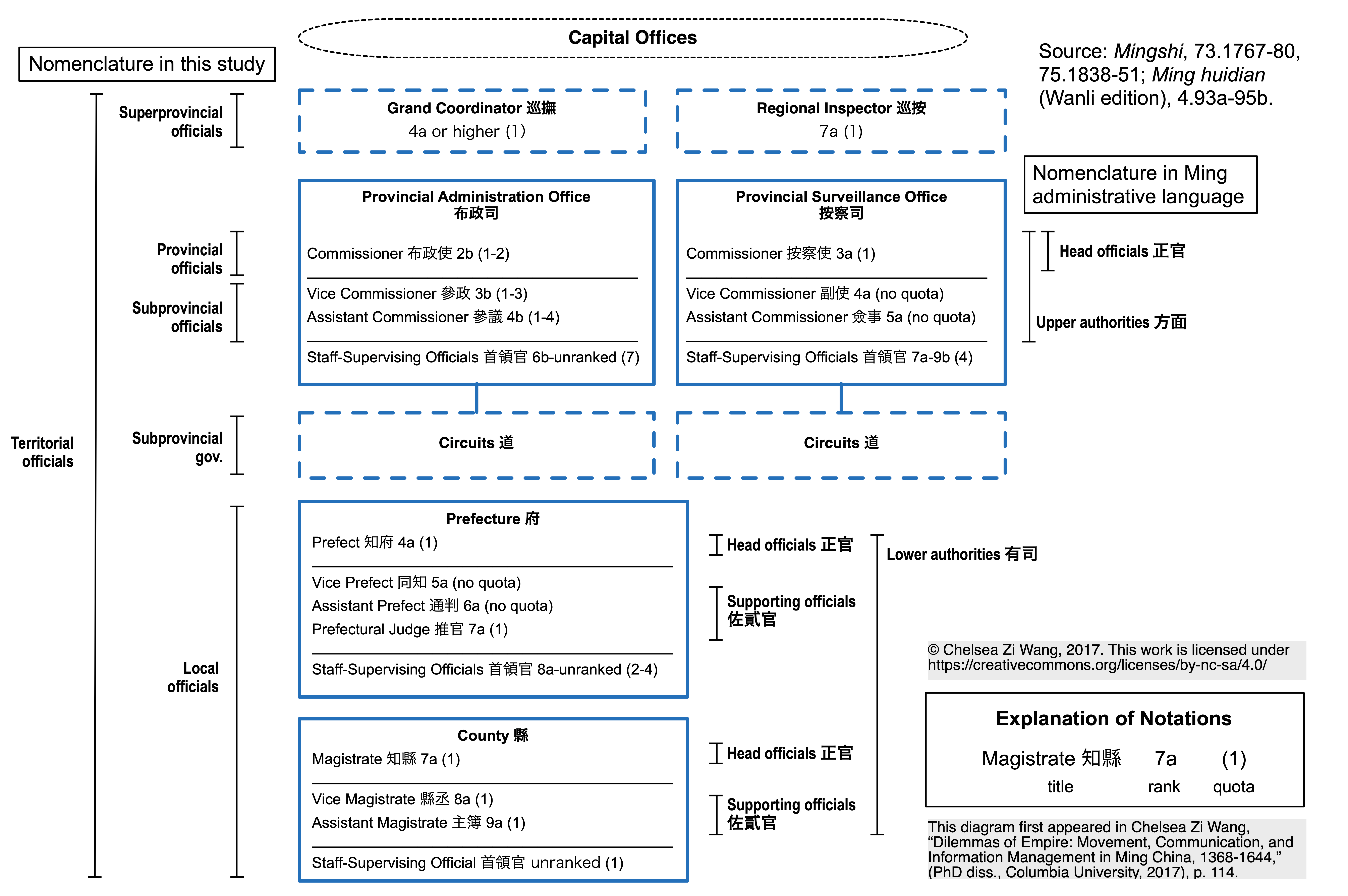

Structure of the Ming bureaucracy (Image Source)

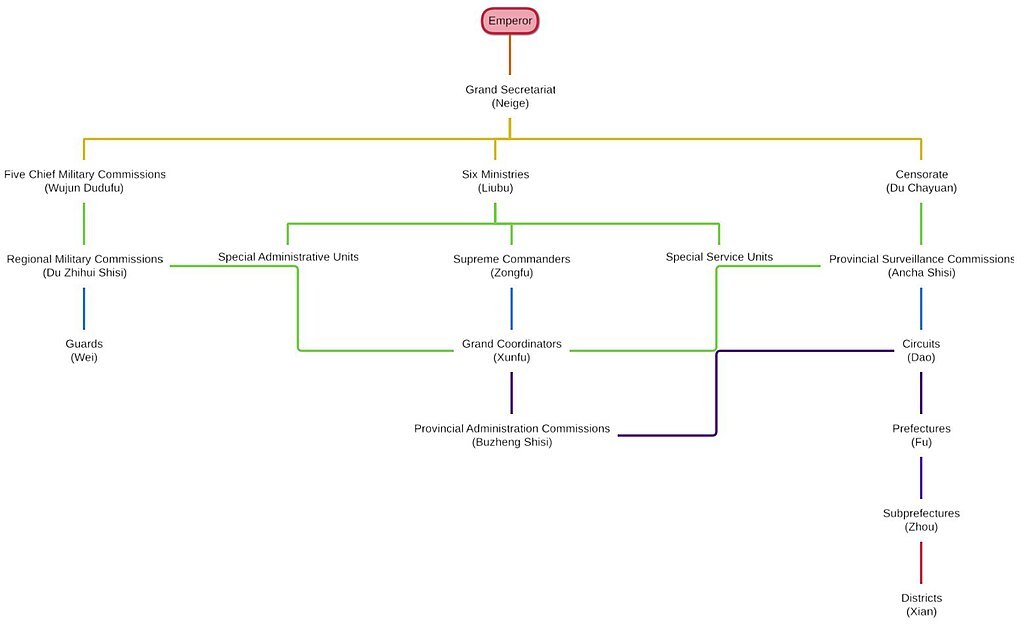

Conceptual map of the Ming territorial bureaucracy (Image by Professor Wang)

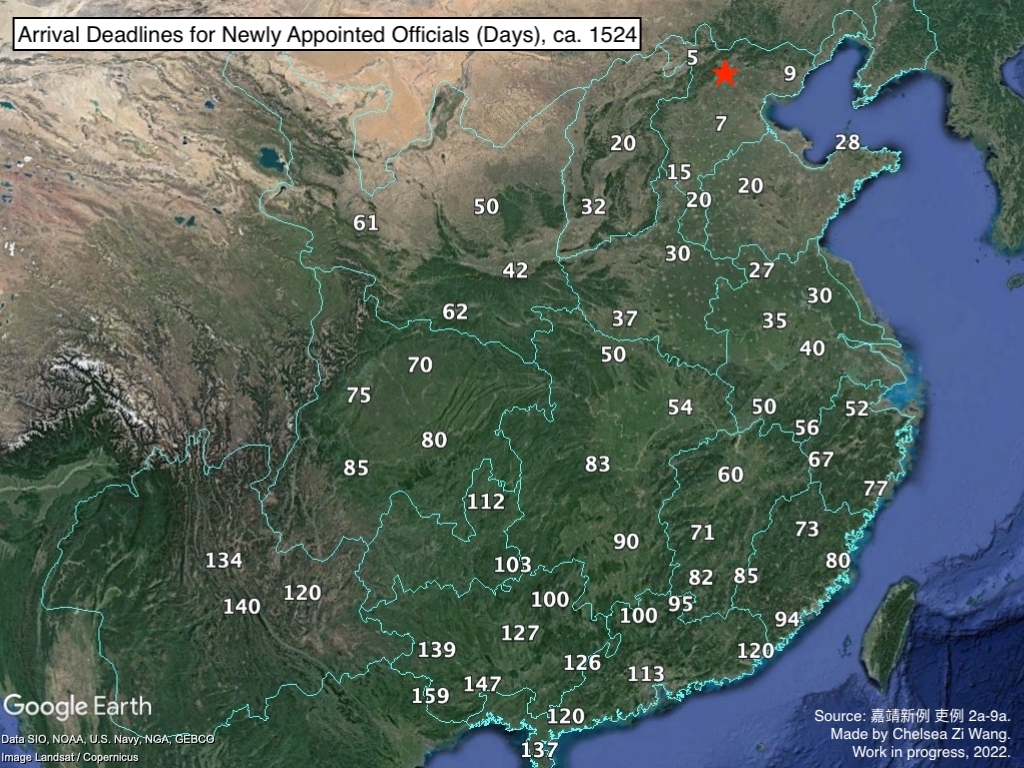

Deadlines for newly appointed officials to arrive at their locations of service. The red star indicates the location of Beijing, the imperial capital (Image by Professor Wang. Please do not cite or circulate without permission)

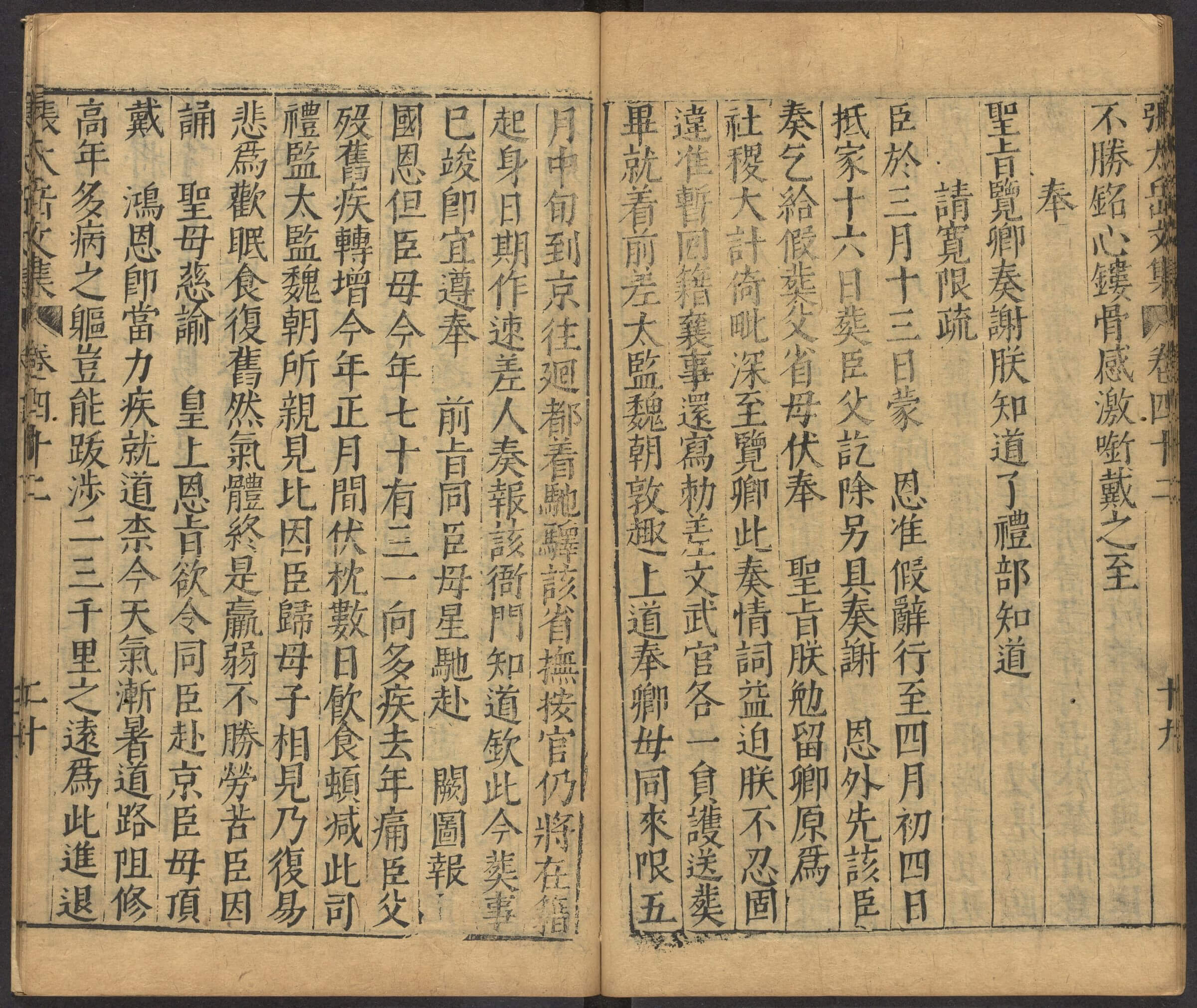

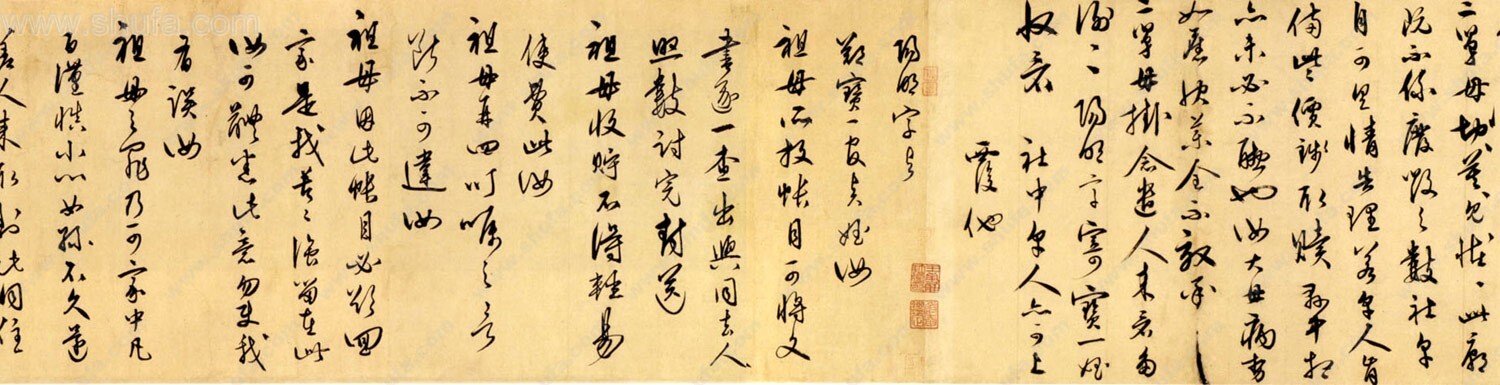

A memorial reproduced in a Ming literary collection. This memorial, written by the controversial Grand Secretary Zhang Juzheng and addressed to the Wanli emperor, contains information about Zhang's speed of travel when he returned to Huguang province to bury his recently deceased father (Image Courtesy of Harvard-Yenching Library's Digital Collections)

Section of a Ming officials' handbook showing information about individual administrative units in Zhejiang province. The text contains information about each prefecture's tax quota, subordinate counties, distance from Beijing, and arrival deadlines for officials traveling from Beijing (Image Courtesy of Harvard-Yenching Library's Digital Collections)

References

Dardess, John W. Ming China, 1368-1644: A Concise History of a Resilient Empire. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield, 2012.

Guo Hong 郭红 and Jin Runcheng 靳润成. Zhongguo xingzheng quhua tongshi: Mingdai Juan 中国行政区划通史: 明代卷. Shanghai: Fudan daxue chubanshe, 2007.

Hucker, Charles O. “Governmental Organization of the Ming Dynasty.” Harvard Journal of Asiatic Studies 21 (1958): 1–66.

Nimick, Thomas G. Local Administration in Ming China: The Changing Role of Magistrates, Prefects, and Provincial Officials. Minneapolis: Society for Ming Studies, 2008.

Schneewind, Sarah. “Pavilions to Celebrate Honest Officials: An Authenticity Dilemma in Fifteenth-Century China.” Journal of the Economic and Social History of the Orient 65, no. 1-2 (2022): 164–213.

Shen Bin 申斌. “Mingdai Guanwenshu jiegou jiedu yu xingzheng liucheng fuyuan: yi Shandong jinghuilu de zuanxiu wei li” 明代官文书结构解读与行政流程复原—以《山东经会录》的纂修为例. Anhui shifan daxue xuebao: renwen shehui kexue ban 44, no. 6 (2016): 749–56.

Wang, Chelsea Zi. “Dilemmas of Empire: Movement, Communication, and Information Management in Ming China, 1368-1644,” PhD diss., Columbia University, 2017.

Yu Jindong 余劲东 and Zhou Zhongliang 周中梁. “Mingdai chaojin kaocha chengxian zhi yanjiu: yi Tongma bian wei zhongxin de tantao” 明代朝觐考察程限之研究——以《铜马编》为中心的探讨. Lishi jiaoxue wenti (2015): 26, 69–73.

Zhang, Ying. Confucian Image Politics: Masculine Morality in Seventeenth-Century China. Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2017.

Sunday Jul 31, 2022

The Ming in the Southwest: Conquest, Rule, and Legacy

Sunday Jul 31, 2022

Sunday Jul 31, 2022

In 1381, Ming armies marched into Yunnan and Guizhou and within a year had deposed the Mongol Yuan's Prince of Liang, who had been enfeoffed there by the Yuan court. The Hongwu's emperor's decision to annex Yunnan and Guizhou and establish Ming administration there was unusual, for before the Mongols conquered it in the mid-1250s, the area had never been under the control of a China-based empire. It was more Southeast Asian in character than it was Chinese in character. Yet for decades, the scholarly community has neglected the study of the southwest. In this episode, Sean Cronan will discuss the Ming's rule in the region, how the early Ming court reshaped the interstate environment of Southwest China and Upper Mainland Southeast Asia, as well as some of the legacies that the early Ming left on the region.

Contributors

Sean Cronan

Sean Cronan is a Ph.D. student at the University of California, Berkeley. His work focuses on East and Southeast Asian diplomatic encounters from the thirteenth to eighteenth centuries, tracing the development of new shared diplomatic norms following the Mongol conquests of Eurasia, as well as how rulers and scholar-officials in the Ming (1368- 1644) and Qing Dynasties (1644-1911) institutionalized and challenged these new norms. He explores how ideas of multipolarity, regime legitimacy, and the makeup of the interstate order came under debate throughout the Mongol Empire, Ming China, the Qing Empire, Chosŏn Korea, Dai Viet (Northern Vietnam), Japan, the Ayutthaya Kingdom of Thailand, the Pagan Kingdom of Burma, and beyond. He works with sources in Chinese (literary Sinitic), Japanese, Thai, Burmese, Manchu, and Dutch.

Yiming Ha

Yiming Ha is a Ph.D. candidate in the Department of History at the University of California, Los Angeles. His current research is on military mobilization and state-building in China between the thirteenth and seventeenth centuries, focusing on how military institutions changed over time, how the state responded to these changes, the disconnect between the center and localities, and the broader implications that the military had on the state. His project highlights in particular the role of the Mongol Yuan in introducing an alternative form of military mobilization that radically transformed the Chinese state. He is also interested in military history, nomadic history, comparative Eurasian state-building, and the history of maritime interactions in early modern East Asia. He received his BA from UCLA and his MPhil from the Hong Kong University of Science and Technology.

Credits

Episode No. 13

Release date: July 31, 2022

Recording location: Los Angeles/Berkeley, CA

Bibliography courtesy of Sean Cronan

Images

Cover Image: A Buddhist monastery in Xishuangbanna (Sipsongpanna), located in Yunnan at the border with Laos and Myanmar. Note the distinct Southeast Asian style architecture. In Ming times this area was called Cheli 車里 and a native official ruled here on behalf of the Ming court. Today it is classified as an autonomous region for the Dai/Tai ethnic group. (Image Source)

https://i.imgur.com/tn3BrKI.jpg

A 1636 Ming map of Yunnan, from the Zhifang dayitong zhi 職方大一統志. Due to the large file size, it cannot be uploaded here. Please click on the link above to view it. The yellow rectangle denotes the location of Kunming, the prefectural seat of Yunnan. Red squares represent major settlements.

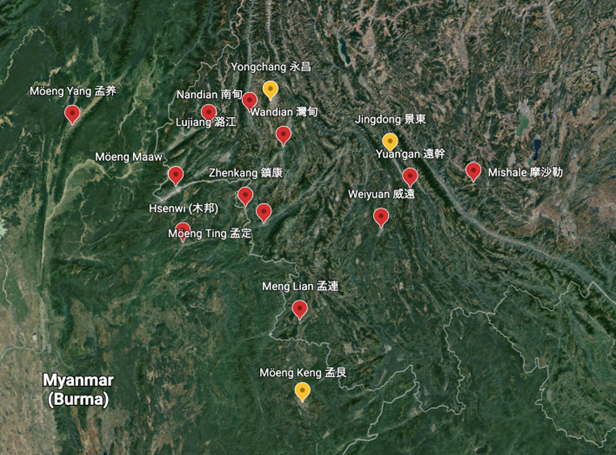

Map of the Möeng Maaw Empire at its greatest extent in 1398. . Areas in red were either governed by a Sa clan appointee or had long been conquered and integrated into the Maaw administrative structure. Areas in yellow were seized by more recent conquest or held only loosely. Map courtesy of Sean Cronan. Please do not cite or circulate.

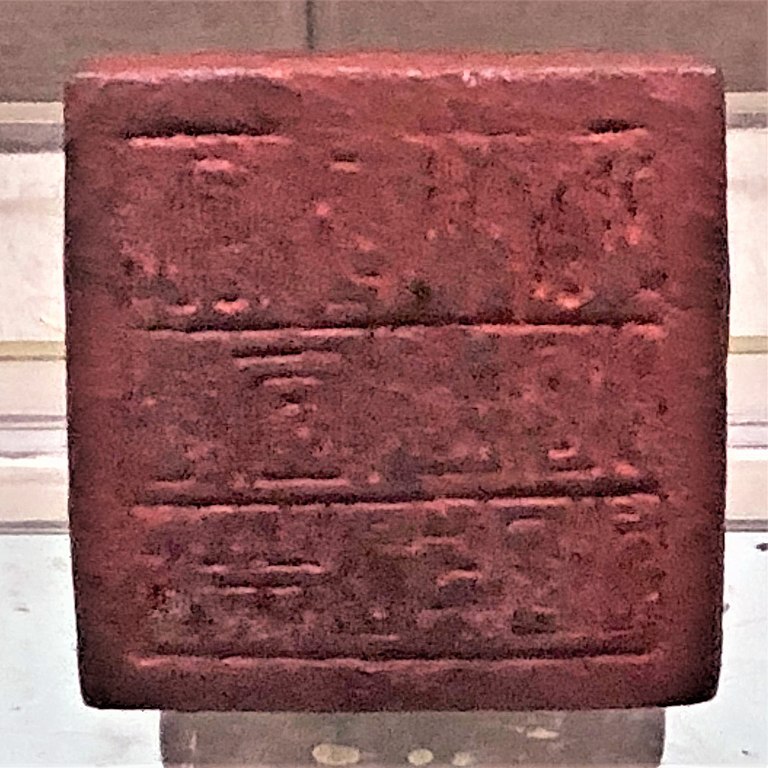

A Yuan seal granted to the native official of Cheli. (Image Source)

References

Daniels, Christian. “The Mongol-Yuan in Yunnan and ProtoTai/Tai Polities during the 13th-14th

Centuries.” Journal of the Siam Society, 106 (2018), 201-243.

Daniels, Christian and Jianxiong Ma, eds. The Transformation of Yunnan in Ming China: from the

Dali Kingdom to Imperial Province. Abingdon, Oxon: Routledge, 2020.

Fernquest, Jon. “Crucible of War: Burma and the Ming in the Tai Frontier Zone (1382-1454).”

SOAS Bulletin of Burma Research, 4:2 (2006), 27-90.

Giersch, Charles Patterson. Asian Borderlands: The Transformation of Qing China's Yunnan

Frontier. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 2006.

Herman, John E. Amid the Clouds and Mist China’s Colonization of Guizhou, 1200–1700. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Asia Center, 2007.

Robinson, David M. In the Shadow of the Mongol Empire: Ming China and Eurasia. Cambridge:

Cambridge University Press, 2020.

Yang, Bin. Between Winds and Clouds: The Making of Yunnan (Second Century BCE to

Twentieth Century CE). New York: Columbia University Press, 2009.

Sunday May 01, 2022

Sunday May 01, 2022

Wang Yangming 王陽明 (born Wang Shouren 王守仁, 1472-1529) is one of the most famous pre-modern Chinese intellectuals and the founder of the School of Mind (心學) of Neo-Confucianism, which was hugely influential in the later half of the Ming Dynasty. In addition to being philosopher, he was also an accomplished statesman, military leader, and calligrapher. In this episode, we speak with Professor George L. Israel, an expert on the study of Wang Yangming, who will introduce us to Wang's life and career, his thoughts and tenants, and his reception in the Ming and the Qing, as well as in neighboring Korea and Japan, and how Wang is viewed in China today.

We apologize for some audio issues with this recording.

Contributors

Professor George L. Israel

Professor George L. Israel is a Professor of History at Middle Georgia State University. His research is primarily on Ming intellectual history and Neo-Confucianism, with a particular focus on the famous Ming Neo-Confucian philosopher Wang Yangming, and he has published extensively about that subject in both English and Chinese.

Yiming Ha

Yiming Ha is a Ph.D. candidate in the Department of History at the University of California, Los Angeles. His current research is on military mobilization and state-building in China between the thirteenth and seventeenth centuries, focusing on how military institutions changed over time, how the state responded to these changes, the disconnect between the center and localities, and the broader implications that the military had on the state. His project highlights in particular the role of the Mongol Yuan in introducing an alternative form of military mobilization that radically transformed the Chinese state. He is also interested in military history, nomadic history, comparative Eurasian state-building, and the history of maritime interactions in early modern East Asia. He received his BA from UCLA and his MPhil from the Hong Kong University of Science and Technology.

Credits

Episode no. 11

Release date: May 1, 2022

Recording location: Los Angeles, CA/Macon, GA

Bibliography courtesy of Professor Israel

Images

Cover Image: An official portrait of Wang Yangming (Image Source)

Grand Hall of Wang Yangming's former residence in Shaoxing (Image Source)

Wang Yangming's tomb at Shaoxing (Image Source)

A copy of Wang Yangming's calligraphy, currently held at Princeton University (Image Source)

References

Bresciani, Umberto. Reinventing Confucianism: The New Confucian Movement. Taipei: Taipei Ricci Institute, 2001.

Ching, Julia. The Records of Ming Scholars. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 1987.

Chow, Kai-wing. The Rise of Confucian Ritualism in Late Imperial China: Ethics, Classics, and Lineage Discourse. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1994.

Chung, So-yi. “Korean Yangming Learning.” In Dao Companion to Korean Confucian Philosophy, 253-284. Edited by Young-chan Ro. Springer, 2019.

Israel, George L. Studying Wang Yangming: History of a Sinological Field. Kindle Direct Publishing, 2022.

____. “The Renaissance of Wang Yangming Studies in the People’s Republic of China.” Philosophy East and West 66, no. 3 (Jul. 2019): 1001-1019.

Jiao Kun 焦堃. Yangming xinxue yu Mingdai neige zhengzhi 陽明心學與明代内閣政治 (The Yangming school of mind and the politics of the grand secretariat during the Ming dynasty). Beijing: Zhonghua Shuju, 2021.

Ogyū Shigehiro 荻生茂博. “The Construction of ‘Modern Yōmeigaku’ in Meiji Japan and Its Impact on China.” Translated, with an introduction, by Barry D. Steben. East Asian History no. 20 (December 2000): 83–120.

Qian Ming 錢明. Wang Yangming ji qi xuepai lun kao 王陽明及其學派論考 (Verification of theories of Wang Yangming and his school of thought). Beijing: Renmin Chubanshe, 2009.

Zhang Kunjiang 張崑將. Yangmingxue zai dongya: quanshi, jiaoliu yu xingdong 陽明學在東亞:詮釋, 交流與行動 (Yangming learning in East Asia: interpretation, exchange, and action). Taipei: Guoli Taiwan Daxue Chuban Zhongxin, 2011.

Saturday Jan 29, 2022

New Narratives on the Late Ming Military: An Interview with Professor Kenneth Swope

Saturday Jan 29, 2022

Saturday Jan 29, 2022

For a long time, Ray Huang's influential book 1587: A Year of No Significance has colored our imagination of the Late Ming, painting the Ming as a state that was stagnant and in decline. Traditional historiography usually focuses on the poor finances of the Ming state, its inability to pay troops, its poor military performance against the peasant rebels and the Manchus, and its factionalism. While all these are true to an extent, more recent scholarships have also uncovered another side to the late Ming - one of military success and military innovation. Professor Kenneth Swope, an expert on Ming military history and author of numerous monographs and articles on the topic, joins us to talk about these new narratives of the late Ming's successes and failures.

Contributors

Professor Kenneth Swope

Professor Kenneth Swope is a Professor of History & Senior Fellow of the Dale Center for the Study of War & Society at the University of Southern Mississippi. He is an expert on Chinese military history, particularly Ming military history and has published numerous monographs, articles, and book chapters on the topic. His major publications include A Dragon’s Head and a Serpent’s Tail: Ming China and the First Great East Asian War, 1592-1598, The Military Collapse of China’s Ming Dynasty, 1618-1644, and On the Trail of the Yellow Tiger: War, Trauma, and Social Dislocation in Southwest China During the Ming-Qing Transition. In addition, he serves as the book review editor for The Journal of Chinese Military History and is a member of the Board of Directors for the Chinese Military History Society.

Yiming Ha

Yiming Ha is a Ph.D. candidate in the Department of History at the University of California, Los Angeles. His current research is on military mobilization and state-building in China between the thirteenth and seventeenth centuries, focusing on how military institutions changed over time, how the state responded to these changes, the disconnect between the center and localities, and the broader implications that the military had on the state. His project highlights in particular the role of the Mongol Yuan in introducing an alternative form of military mobilization that radically transformed the Chinese state. He is also interested in military history, nomadic history, comparative Eurasian state-building, and the history of maritime interactions in early modern East Asia. He received his BA from UCLA and his MPhil from the Hong Kong University of Science and Technology.

Credits

Episode no. 7

Release date: January 29, 2022

Recording location: Hattiesburg, MS/ Los Angeles, CA

Bibliography courtesy of Professor Swope

Images:

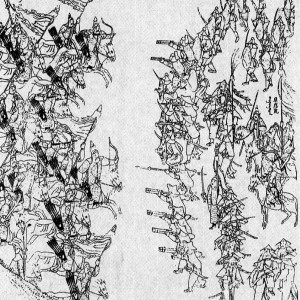

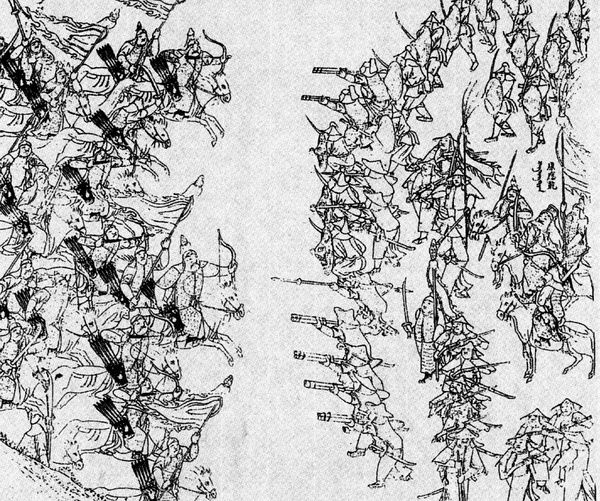

Cover Image: Battle of Sarhu, 1619. Note the use of gunpowder weapons. (Image Source)

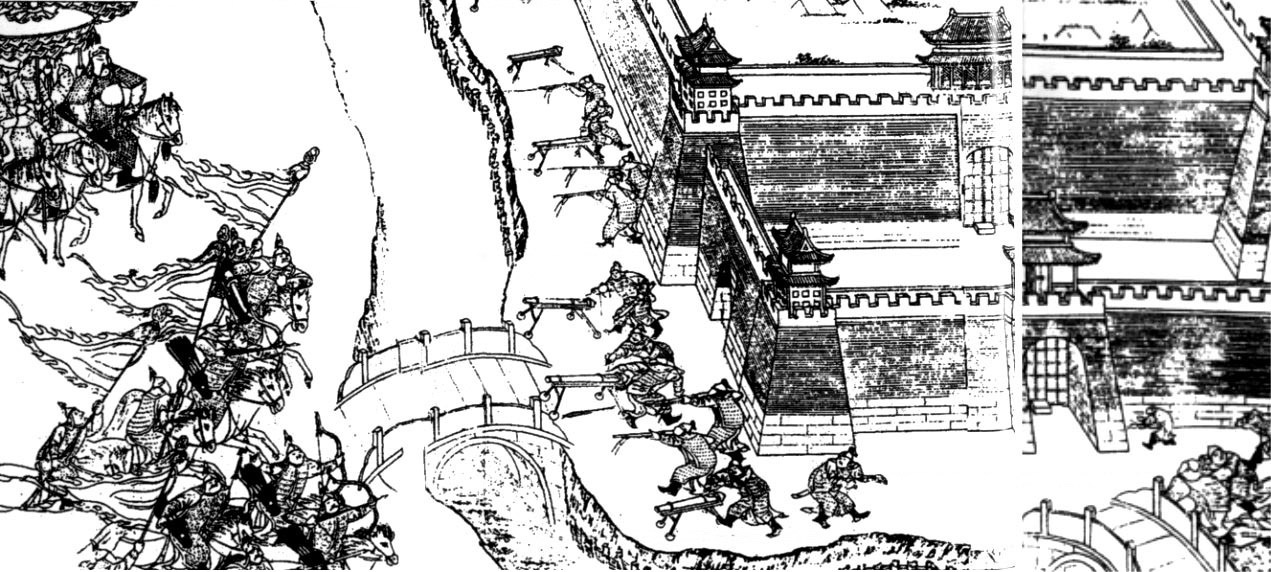

Battle of Liaoyang, 1621. Note the use of gunpowder weapons. (Image Provided by Professor Swope)

Gate at Shanhai Pass (Photograph by Professor Swope)

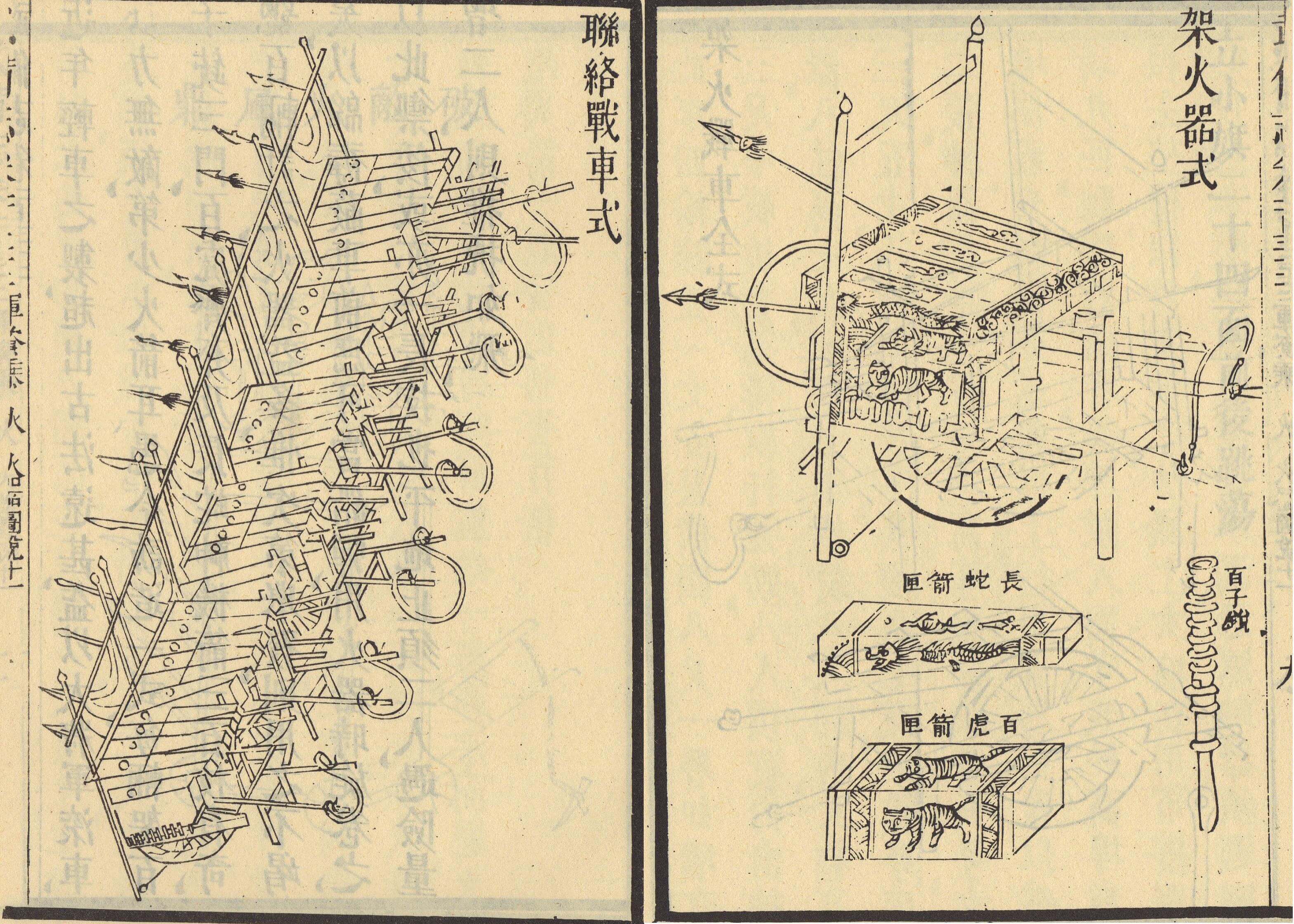

Ming rocket-propelled arrows and launching tube and cart, from the Wubei zhi (for more images of Ming gunpowder weapons, see here)

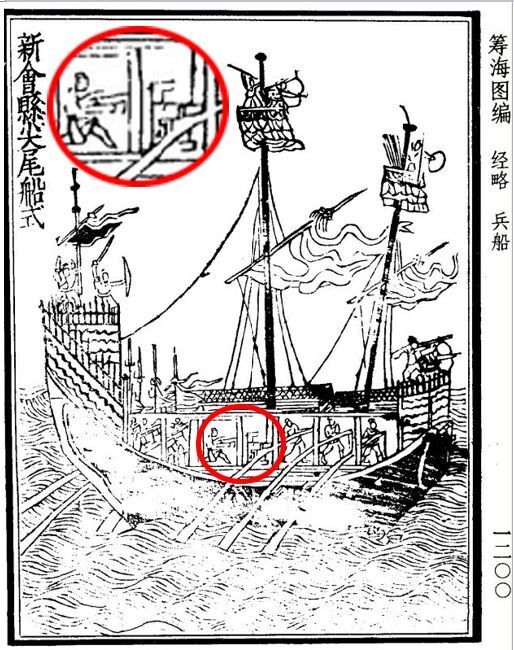

A type of Ming warship from the Chouhai tubian, note the gunner operating a cannon on the lower deck.

References

Andrade, Tonio. Lost Colony: The Untold Story of China’s First Great Victory over the West. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2011.

Fan Shuzhi 樊樹志. Wan Ming shi 晚明史 2 vols. Shanghai: Fudan daxue chubanshe, 2015.

-----. Wanli zhuan 萬歷傳. Beijing: Zhonghua shuju, 2020.

Parsons, James B. Peasant Rebellions of the Late Ming Dynasty. Ann Arbor: Association for Asian Studies, 1993.

Struve, Lynn A. The Southern Ming, 1644-1662. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1984.

Swope, Kenneth M. On the Trail of the Yellow Tiger: War, Trauma, and Social Dislocation in Southwest China during the Ming-Qing Transition. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2018.

-----. The Military Collapse of China’s Ming Dynasty. London: Routledge, 2014.

-----. A Dragon’s Head & a Serpent’s Tail: Ming China and the First Great East Asian War, 1592-1598. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2009.

Wakeman, Jr., Frederic W. The Great Enterprise. 2 Vols. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1985.

Sunday Dec 12, 2021

Sunday Dec 12, 2021

In our previous episodes, the term "tributary system" has come up a few times, yet we've never had the opportunity to explain what exactly it is. To better shed light on this topic, and as part of our exploration of Chinese diplomacy, we interviewed Professor Sixiang Wang, an Assistant Professor of Korean history at UCLA who specializes in the diplomatic relationship between Chosŏn Korea and Ming China and Early Modern East Asia. In this episode, Professor Wang will first explain what the tributary system is as a historiographical concept and how it is often used to view China's diplomatic engagement with the outside world, before giving us a more detailed look into the diplomacy between Chosŏn and Ming and how this diplomatic interaction complicates the simple narrative of the tributary system.

P.S. Don't forget to check out this awesome podcast on the steppe nomads at Nomads and Empires!

Contributors

Sixiang Wang

Sixiang Wang is an Assistant Professor in the Department of Asian Languages and Cultures at UCLA. He is a historian of Chosŏn Korea and early modern East Asia, and his research interests also include comparative perspectives on early modern empire, the history of science and knowledge, and issues of language and writing in Korea’s cultural and political history. His current book project reconstructs the cultural strategies that the Korean court deployed in its interactions with Ming China through an examination of poetry-writing, gift-giving, diplomatic ceremony, and historiography, and it underscores the centrality of ritual and literary practices in producing diplomatic norms, political concepts, and ideals of sovereignty in the construction of a shared, regional interstate order.

Yiming Ha

Yiming Ha is a Ph.D. candidate in the Department of History at the University of California, Los Angeles. His current research is on military mobilization and state-building in China between the thirteenth and seventeenth centuries, focusing on how military institutions changed over time, how the state responded to these changes, the disconnect between the center and localities, and the broader implications that the military had on the state. His project highlights in particular the role of the Mongol Yuan in introducing an alternative form of military mobilization that radically transformed the Chinese state. He is also interested in military history, nomadic history, comparative Eurasian state-building, and the history of maritime interactions in early modern East Asia. He received his BA from UCLA and his MPhil from the Hong Kong University of Science and Technology.

Credits

Episode No. 4

Release date: December 12, 2021

Recording location: Los Angeles, CA

Bibliography courtesy of Professor Sixiang Wang

Images

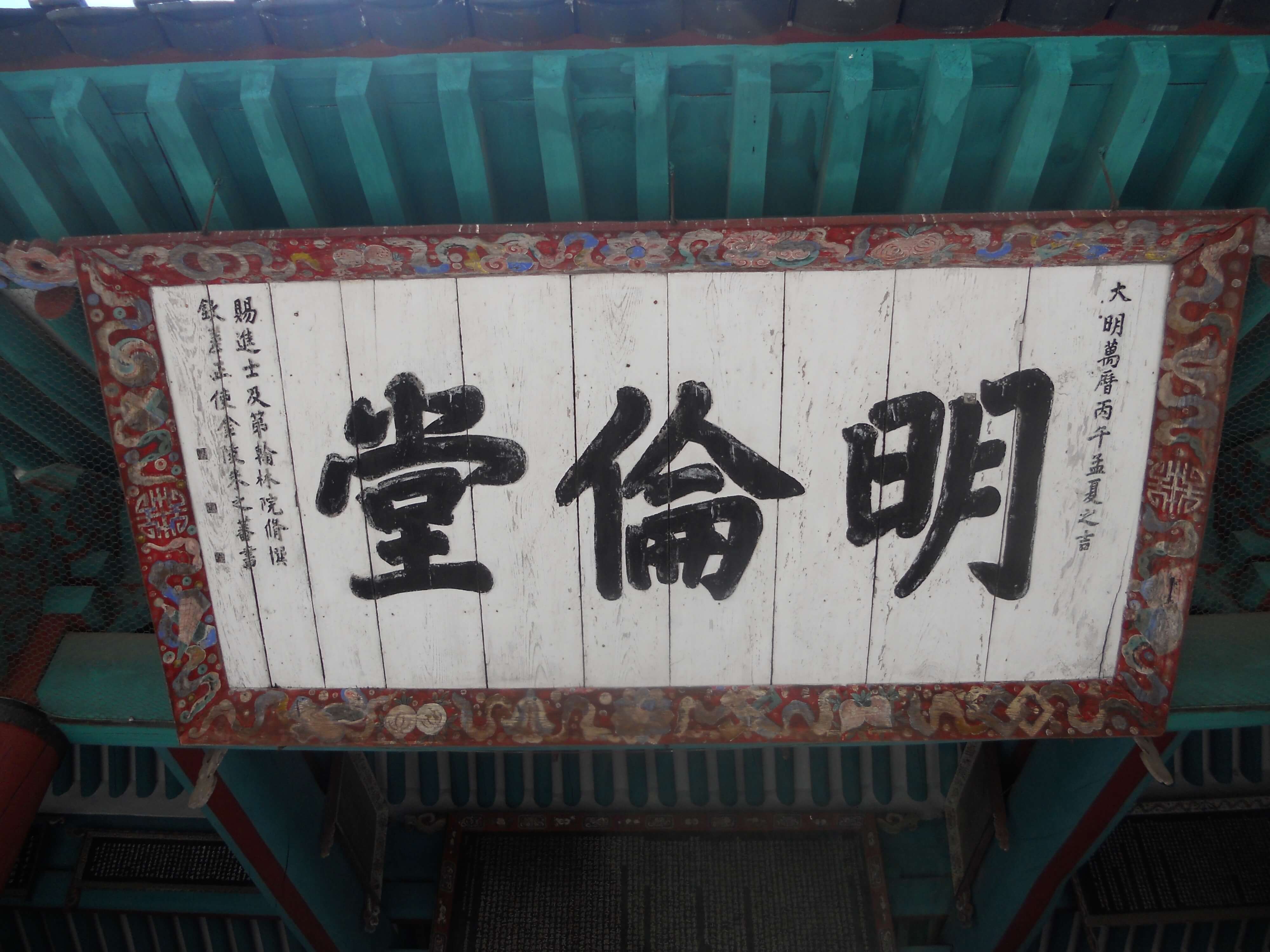

Cover Image: "Myŏngnyun Hall" 明倫堂, Hanging board with calligraphy by the 1606 Ming envoy Zhu Zhifan 朱之蕃, Sunggyun'gwan University (photographed by Prof. Sixiang Wang)

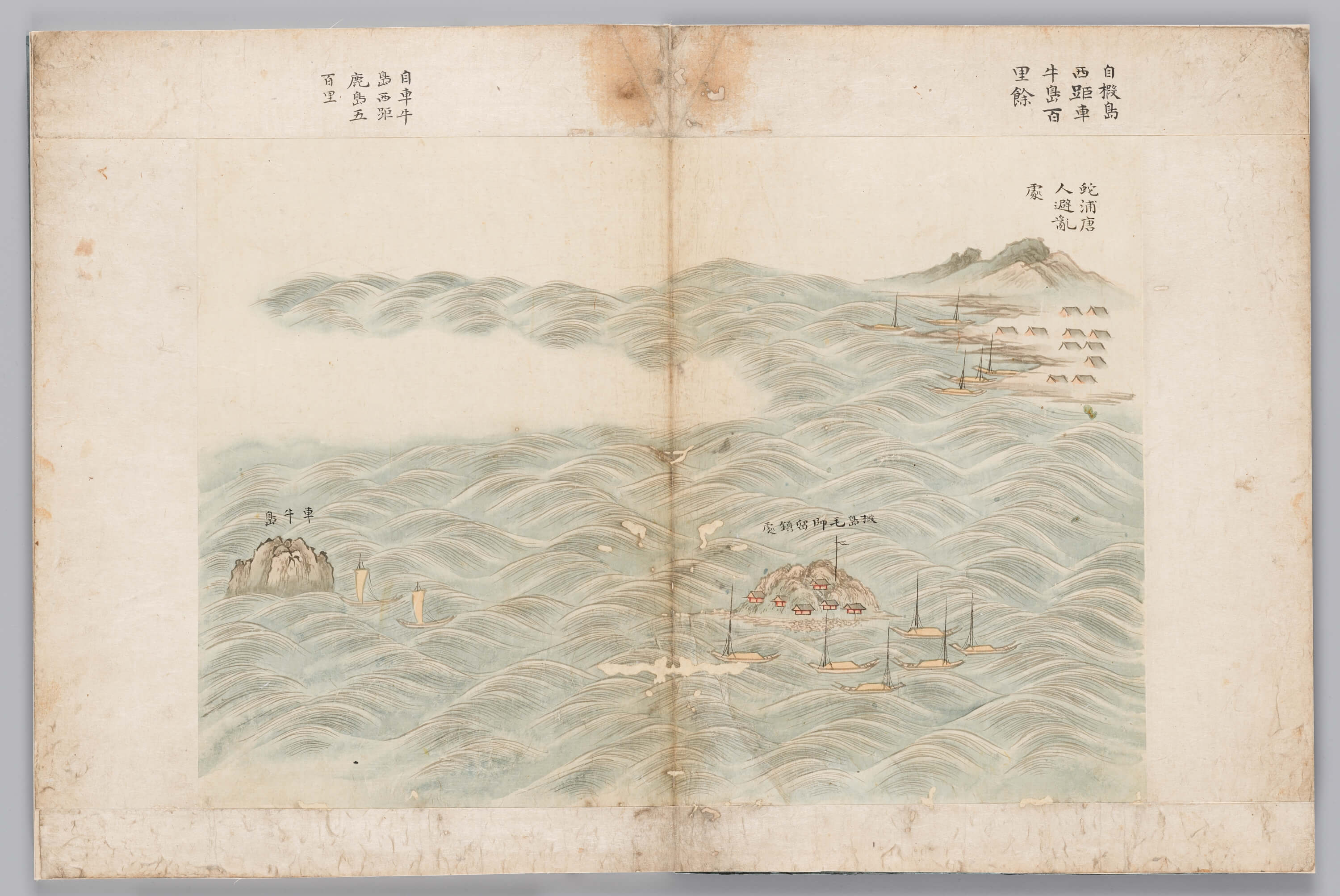

Chosŏn Envoys Traveling to Ming China by Sea, by Yi Tŏkhyŏng. It details an envoy mission which travelled to Ming China in 1624. One of a set of 25 paintings, currently held in the National Museum of Korea and reproduced with permission here (Image Source)

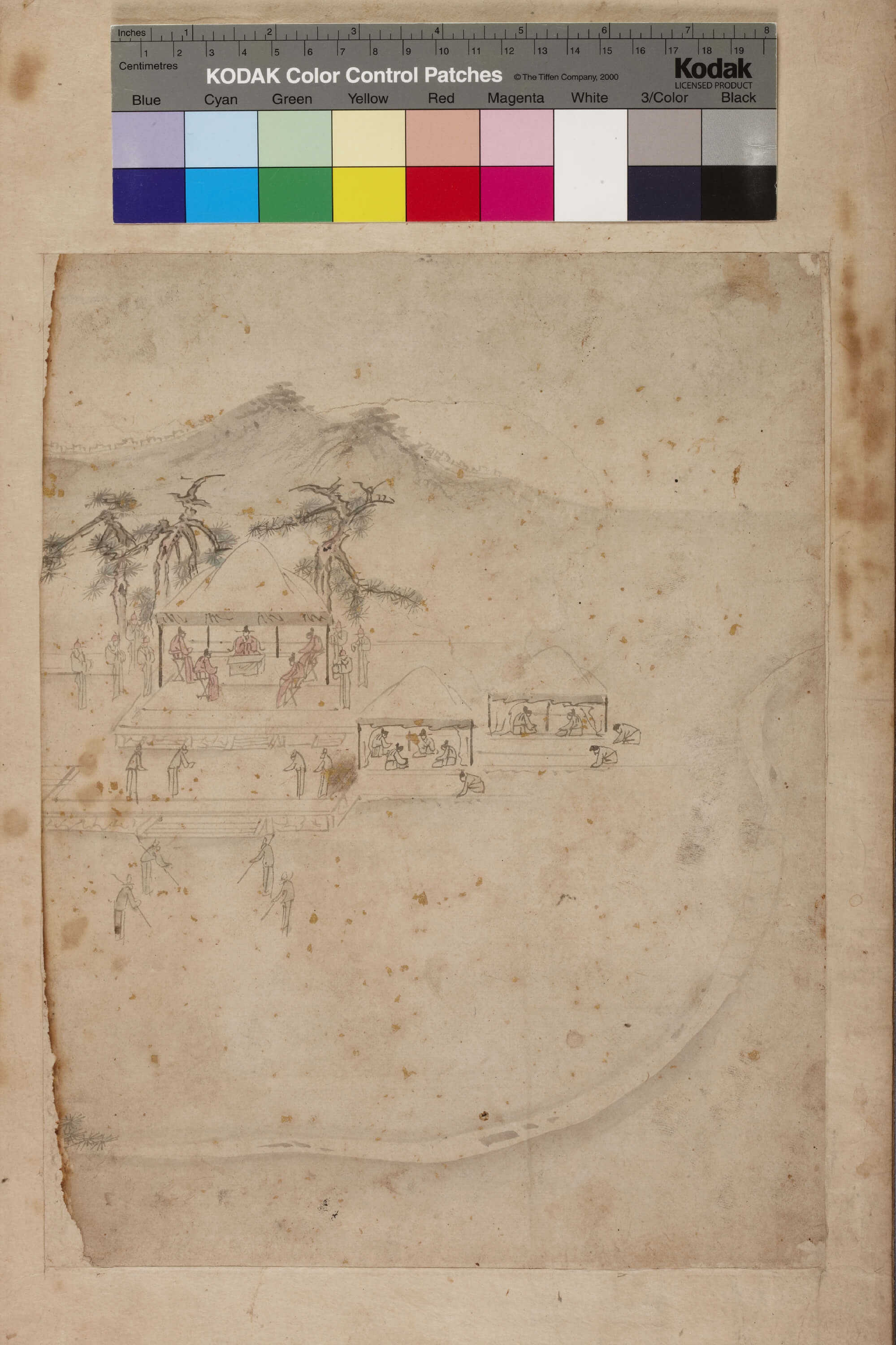

Reception of Ming envoys, unknown painter, currently held in the National Museum of Korea and reproduced with permission here (Image Source)

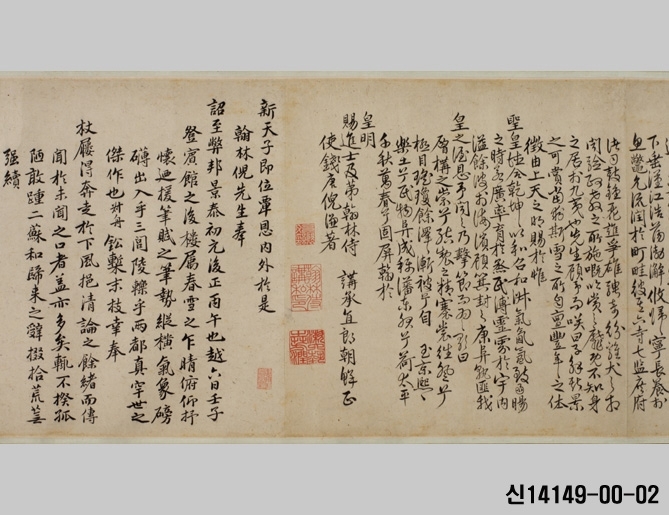

Collection of Poems by a Ming Envoy and the Scholars of the Chosŏn Dynasty. A collection of poetic exchange by the 15th century Ming envoy Ni Qian 倪謙 and three Korean scholars, currently held in the National Museum of Korea (Image Source)

Select Bibliography